I buy a lot of books. Mostly the printed, 3-dimensional variety, composed of paper and ink. Rarely, rarely do I dip into e-books. I did at one time own a Kindle, and I’ve flirted with the idea of upgrading to a Paperwhite e-reader, or possibly a Nook. But I’ve never been able to actually do it.

I like to think it isn’t because of my age. I’m a proud Xennial, born into the weird micro generational space between Gen Xers and the Millennials. I remember rotary phones and record players. But I also started using computers in grade school, and by the time high school rolled around, the World Wide Web was a thing. It had chatrooms, games, mp3 files (I smile every time I remember Napster and dial-up internet!), blogs, and websites. There was barely any e-commerce. There was no social media at all. On the whole, I remember it as being pretty great.

In adulthood, I’ve built most of my career around digital spaces, so it’s not a dislike for technology or a reluctance to try new products that holds me back. I don’t think it’s nostalgia, either. I suspect something deeper is in play, something that has layers to it.

It might be this: books leave a paper trail. They can show you not only who read them, but how they were read. Bookplates and inscriptions name previous owners. They can indicate if the book was a gift. Notes or annotations reveal a reader’s reactions to the text. Even – heaven forbid! – dog-eared pages offer clues as to where a reader had been and where they might want to return.

I didn’t learn the word for readers’ scribblings until I was in my twenties and working at the Folger Shakespeare Library. They’re called marginalia. And as soon as I heard the term, I loved it. It gave a name to these literary curiosities. It let me know I wasn’t the only one who found them fascinating.

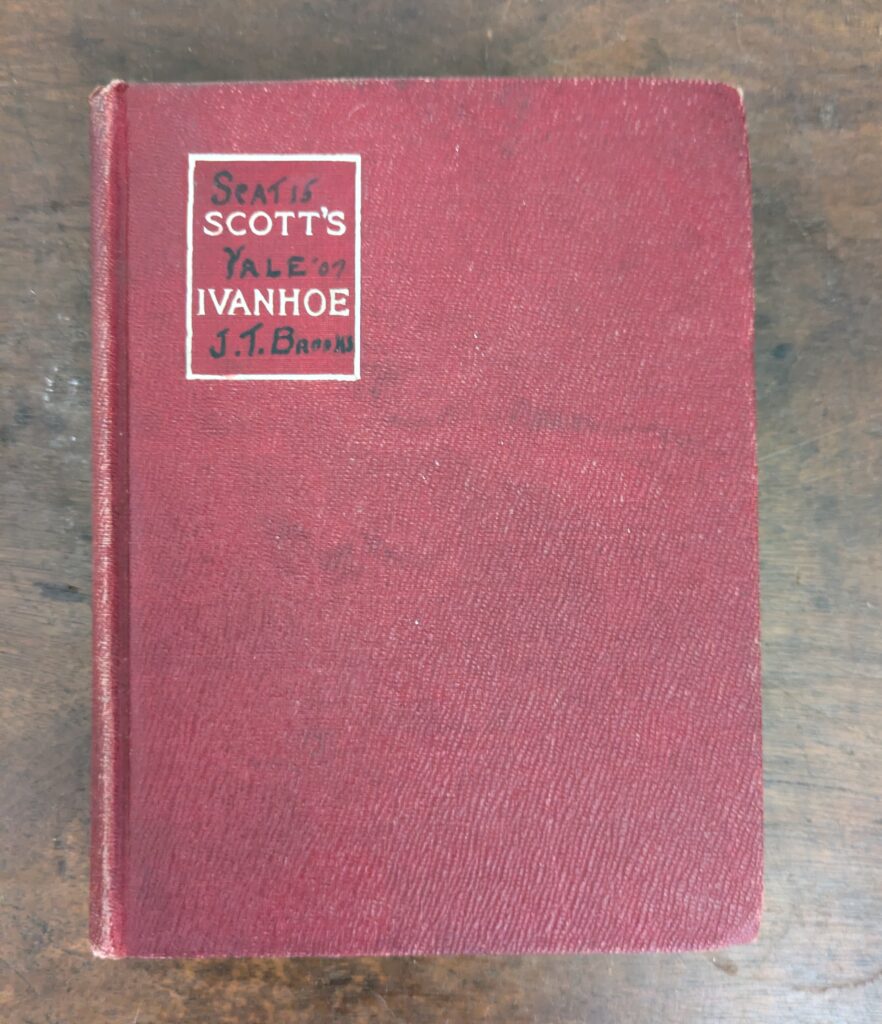

Marginalia isn’t just made by bookish types. World figures like Henry VIII and Josef Stalin marked up their books. So did Jane Austen and Charles Darwin. Ordinary people leave their traces as well, such as a student named J. T. Brooks who attended Yale in the early 1900s and left extensive notes within the covers of his copy of Ivanhoe, which now rests on my bookshelf. (I am assuming Brooks was male since Yale did not begin admitting women until 1969).

As I think about it, almost any handwritten record offers an invitation to reflect, or even play detective (I’ve contacted Yale to see if there are any student records on Brooks). I remember the joy I took in reading a diary from 1868, and how holding the actual book in my hands made the experience infinitely more personal.

My fascination isn’t only for consuming marginalia. I’m guilty of producing it myself. My college textbooks are full of penciled notes and occasionally marked by highlighters. Opening the pages and seeing these traces of my twenty-something self lets me view not only where I’d been, but gives me a glimpse of who I’d been, too.

I’m not in the habit of making much in the way of marginalia these days. I’m far more likely to jot my thoughts down on a sticky note of either the paper or virtual kind. But I am as fond as ever of physical books. Perhaps because there’s always a chance that while I’m reading, I too will have something to say.